Dengue is not 'next Covid-19', but threat must still be taken seriously: Experts

Although dengue is not the next Covid-19, the threat it poses must still be taken seriously, experts told The Straits Times.

This is because the disease can still kill, and may also impose a burden on hospitals and the economy here.

However, the experts added that because of the nature of dengue, any public health measures taken are unlikely to be the same as those implemented to combat the coronavirus pandemic.

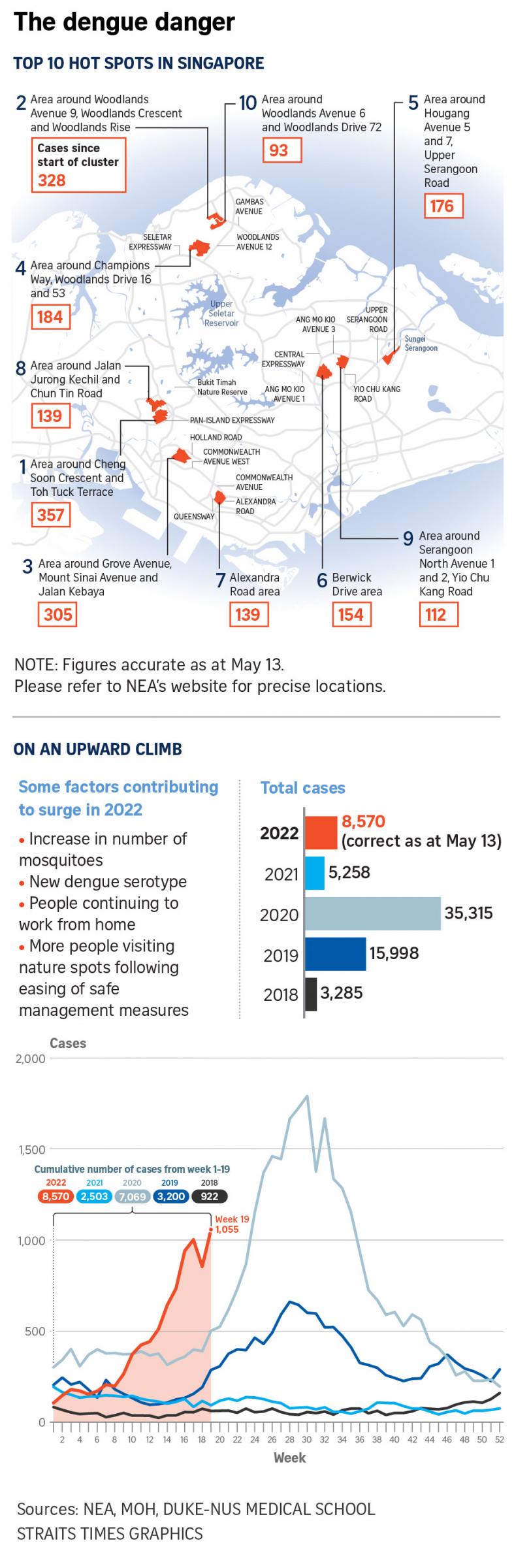

Since the start of the year, the Republic has recorded more than 8,500 cases of dengue. This is more cases than for the entire 2021, and a higher caseload than the total for the same period each year from 2018 to 2021.

The National Environment Agency (NEA) has repeatedly called for vigilance in the community, warning that Singapore could see a major dengue outbreak this year, especially since the number of cases has been rising sharply even before the traditional peak dengue season from June to October.

When asked about the surge and its potential impact on public health here, Associate Professor Alex Cook, vice-dean of research at the National University of Singapore's (NUS) Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, said: "I don't think dengue will be the next Covid-19, and we will not need the same kind of broad restrictions on liberties as we did over the last few years to respond to it."

This is because of key differences between the diseases. Covid-19, he pointed out, is very transmissible and typically gets transmitted from person to person.

This meant that before vaccines were available, the only way to stop it was through non-pharmaceutical interventions, such as safe management measures, which required members of the public making great changes to their daily lives.

However, as dengue is transmitted to humans from the bite of an infective mosquito, it can be controlled through environmental, non-pharmaceutical measures.

"The burden of these on the general population is much smaller, because much of it is done by the government rather than individuals," he said.

"However, we should not forget that dengue can make you very badly sick, and it can, and does, kill some of those who get infected," he added.

Dr Ruklanthi de Alwis, senior research fellow with Duke-NUS Medical School's Emerging Infectious Diseases Programme, agreed.

She noted that during the circuit breaker period, when Covid-19 control measures were at their tightest, the prevalence of dengue did not decrease despite infections from other diseases dropping.

"The control efforts for Covid-19, which is a respiratory pathogen, will not work for dengue," she added.

However, dengue is still not a disease to be taken lightly. Prof Cook said dengue could impact Singapore in three ways.

First, some dengue cases still need to be hospitalised, so when there is a big outbreak, the number of hospitalised dengue patients can affect hospitals' regular functioning by taking up beds that would be used for other conditions.

Second, dengue is a serious condition that could lead to patients requiring time off work or having to find alternative care arrangements for their families.

Third, dengue has economic cost for a society. Citing a recent study by the NEA, Prof Cook said that dengue may cost the economy more than $100m a year.

Dr de Alwis, who is also a senior research fellow at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Viral Research and Experimental Medicine Centre, highlighted that about 75 per cent of dengue cases are asymptomatic or otherwise unreported - allowing them to act as a large hidden reservoir of the virus for mosquitoes to get infected and worsen the problem.

Aside from hidden transmission in humans, there is also transmission between infected mosquitoes and animals in the wild, which is not as well monitored and could potentially result in mutations emerging.

Prof Cook said that this year's surge in cases is likely the combined effect of various factors, rather than one single cause.

Dr de Alwis cited several factors, such as an increase in mosquitoes, the prevalence of a new dengue serotype - DenV-3 - to which not many here have immunity, a proportion of the population continuing to work from home, as well as more people going out to places in nature following the easing of safe management measures.

Asked why Singapore has been unable to eradicate dengue, both experts said that the nation has actually done very well.

But Prof Cook said the country has been the "victim of its past successes", which have led to lower levels of immunity in the population as a result of effective mosquito control campaigns in the past.

Noting that there is a reservoir of the disease in animals as well as people here, Dr de Alwis added: "As long as there are mosquitoes that can transmit... as long as we don't have vaccines that can protect the population, dengue will still be around."

She explained that being infected with dengue once grants immunity against all four serotypes for around one year, although this varies from person to person.

Afterwards, someone will still have lifelong immunity from the serotype they were infected with, but their next infection with a different serotype is likely to be more severe.

Prof Cook said that there are three things people can do to protect themselves from dengue aside from doing the mozzie wipeout.

First, install NEA's MyEnv app to be alerted of nearby clusters.

Second, consider installing mosquito netting over windows to keep the insects out.

Third, if there is a cluster nearby, wear long pants and sleeves, apply repellent, and spray insecticide in dark places at home, as mosquitoes like to rest there after a blood meal.

Dr de Alwis said: "Just because dengue is an old enemy, we shouldn't forget it does kill, especially with new serotypes - so people should be aware."

Get The New Paper on your phone with the free TNP app. Download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store now