Halloween crowd crush in Seoul was ‘absolutely avoidable’, experts say

SEOUL – When K-pop group BTS staged a show in South Korea that drew a crowd of 55,000, police were ready, assigning 1,300 officers to keep people safe.

And when political protests are held, however modest in size, the country’s police are famous for laying careful plans to make sure crowds do not get out of control.

But that did not happen on Saturday night, when tens of thousands of boisterous young Koreans, freed at last of pandemic restrictions, surged into a Seoul nightlife neighbourhood to celebrate Halloween. The police had assigned just 137 officers – and most of those were ordered not to direct the throngs of people but to look out for crimes such as sexual harassment, theft and drug use.

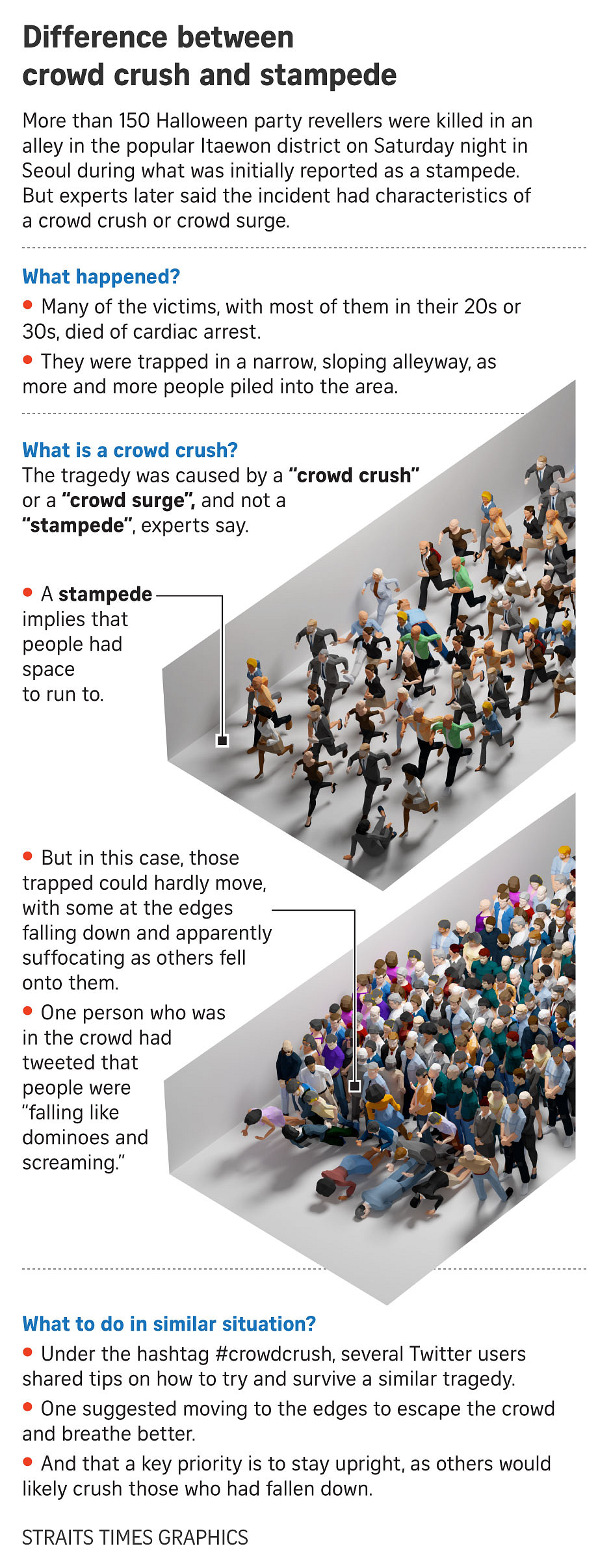

By the next morning, the human cost of those decisions was clear: More than 150 people died in a narrow alleyway in Itaewon, the popular entertainment district in central Seoul where they had crammed in to enjoy an October evening out.

Although government officials have been mostly tight-lipped about what went wrong that night – saying only that they were caught off guard – many are already placing blame for one of the worst peacetime disasters in South Korea’s history on the failure to police the crowd, even as it became evident that things were getting out of control.

“This is clearly a man-made disaster,” Ms Park Ji-hyun, a leader of the opposition Democratic Party, said in a Facebook post. “The government must take responsibility for failing to control the crowd, even when a bigger crowd was expected this year than last.”

The crowd issues that come with a pop performance, of course, are not the same as a party in the streets. Unlike the BTS concert, government officials point out, the gathering in Itaewon was spontaneous. There were no sponsors or organisers, who are required by law to discuss safety measures with the police when they host large events that need traffic and crowd control.

But the police themselves knew a large crowd would gather, if not just how large it would become. In a news release on Thursday, the Yongsan police station, which oversees the neighbourhood, said its top priority was to “secure citizens’ safety and order.”

But it appears they failed to take fundamental steps to prepare. Crowd control was a “parallel job”, not the main focus, said a police officer who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the investigation is still underway.

Even on an ordinary weekend, the neighbourhood attracts a crowd. But this promised to be no ordinary weekend, and while the investigation was still continuing, questions were being raised on Monday about why no police officers were in Itaewon to provide crowd control at a well-known chokepoint near a busy subway station exit and a tight alleyway known for its high foot traffic.

As South Korea grappled to understand how a tragedy of this scale could have happened, no government agency seemed prepared to take full responsibility for the scores of people who were killed on one of the busiest nights of the year in Itaewon, although there were signs of division within the governing camp.

South Korea’s home minister, Mr Lee Sang-min, said police forces were overextended throughout the city Saturday to deal with large anti-government and other protest rallies, which have grown in recent months. But, he said, “I doubt that the problem in Itaewon could have been solved even if we dispatched police and firefighters in advance.”

In a radio interview, Mr Kim Gi-hyeon, a senior leader of President Yoon Suk-yeol’s governing People Power Party, said Mr Lee should “watch his mouth”, and blamed local police for failing to control the crowds.

On Monday evening, police were still interviewing witnesses and scrutinising reams of security camera footage.

They had expected a crowd of about 100,000 people each day during the Halloween weekend, but according to traffic data from the Seoul subway, 130,000 passengers used the station in Itaewon on Saturday, compared with 96,000 per day during the Halloween weekend in 2019 and 60,000 to 80,000 per day during the Halloween weekends during the coronavirus pandemic. Last year, only 85 officers were deployed.

Those eager to celebrate Halloween in Itaewon often travel to the neighbourhood by subway to avoid the district’s infamous traffic jams. Subway Exit No. 1 disgorges hordes of passengers all at once. Many head straight to a nearby 10-foot-wide, 130-foot-long, sloping alleyway because it is a shortcut to the area’s hip bars, restaurants and nightclubs.

By about 10pm Saturday, hundreds of people, most of them in their 20s and 30s, were caught there, barely able to breathe or move and with no way to escape. On one side was a line of bars and shops already packed with people who were unable to make room. On the other was the tall wall of the Hamilton Hotel.

Waves of people pushed up and down the slope, jostling to go in opposite directions, while music blaring from bars and clubs drowned out cries for help from those who were suffocating.

Crowd-control experts say police and local officials should have identified the alleyway as a dangerous bottleneck and taken precautions, but neither the police, the city of Seoul nor the central government had a crowd-control plan in place. And with Halloween in Itaewon having no official sponsor, there were no organisers present to direct traffic.

Officials and organizers must learn to watch dense gatherings of people carefully, said Dr Milad Haghani, a senior lecturer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney who researches crowd safety.

“I really believe that we need to learn from past events and use those experiences from the past to prevent incidents such as what happened in Seoul,” Dr Haghani said by e-mail. “This was absolutely avoidable.”

Get The New Paper on your phone with the free TNP app. Download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store now