GetLit! Modern Myths: Hou Yi

Everywhere Hou Yi* went, his camera went too. It was a gift from his wife, one she pushed into his hands at the airport, saying, Take pictures of everything, show me everything while I'm not there.

So he tried.

He took photographs of the cathedrals bombed wide open and of ducks by the pond waiting for the earth to hatch.

He sent his wife pieces of the sky at seven in the morning, brilliant blue rectangles packed in envelopes.

Together with the pictures were short letters: When are you coming? Job is fine. I've found us a nice flat, there are many trees nearby.

He did not mention the pigeon calls in the morning, or the other sounds coming from upstairs - footsteps heavy as giants' or creaks of a bed. Worst of all was the constant drip of voices, loud enough to hear but not enough to distinguish the words.

When the murmurs came filtering through the ceiling, Hou Yi often thought of the time he saw his neighbours, two brothers, talking at midnight.

They lived in the house across and were sitting on the ledge of their bedroom window straddling it so they faced each other. That was years ago, when he was fourteen or fifteen. One of the boys had gone to the same school as Hou Yi.

Over the months, his letters grew shorter, until they only asked, When will you come? Each time she sent reasons for the delay: she would join him when she'd found a job there; the market wasn't looking good; they'd have to save more.From his room, he had watched the brothers talking in low voices, but despite the quiet night, he couldn't hear what absorbed them so deeply. Perhaps the older brother's impending enlistment into the army or astronomy or something else infinitely profound. In the letters to his wife, Hou Yi said none of this. Some things he didn't want to keep, other things he wanted to keep for himself.

Maybe it was his fault, Hou Yi thought one day while walking out from the office for lunch. His entreaties were half-hearted and she sensed it.

He resolved to try harder, when the man at the chip shop asked, Salt and vinegar? He would say yes. Mushy peas? Yes. Curry sauce? Yes. He would say yes to everything this place had to offer. The imminent deep-fried potato made him happy. The sun was warm. Two children were tossing a ball while crossing the street.

Ching chong, one said as they passed him. Go back to China, Steve, the other said. They turned to see if Hou Yi had heard.

Hou Yi forgot about chips. He wanted to say something but didn't know what. Instead he felt for the nearest thing, the camera in his pocket. The boys started to run, their faces split by wide grins. I'll get you, Hou Yi said, though he didn't know how.

The boys ran faster, laughing and shouting, buoyed along by exhilaration.

He held up the camera and zoomed in so he was right behind them, had caught up with them, was close enough to grab them by their hair. Their faces, he saw, were radiant with joy.

Hou Yi zoomed out. Now the boys were very small, their faces smaller, barely a smudge on the viewfinder. Before they disappeared round the corner, he took a photo. A keepsake. It didn't go to his wife.

Some evenings the couple upstairs held parties in their flat. Tonight, Hou Yi went along.

When he heard dishes being set down on the table, he sat cross-legged on the carpet, laid a fork and a knife on either side of his plate, and ate. Afterwards, Hou Yi drank his tea and listened to the mellow voices that seemed to belong around a campfire in the dark. He could see the faces glowing as if lit from the inside. Someone had brought a guitar to the campfire and was strumming it. A man began singing.

Others who knew the lyrics joined in. The song was in Spanish or Portugese, that much Hou Yi could make out, and sounded like one about brotherhood and friendship, or else a song recalling the rolling hills of one's home.

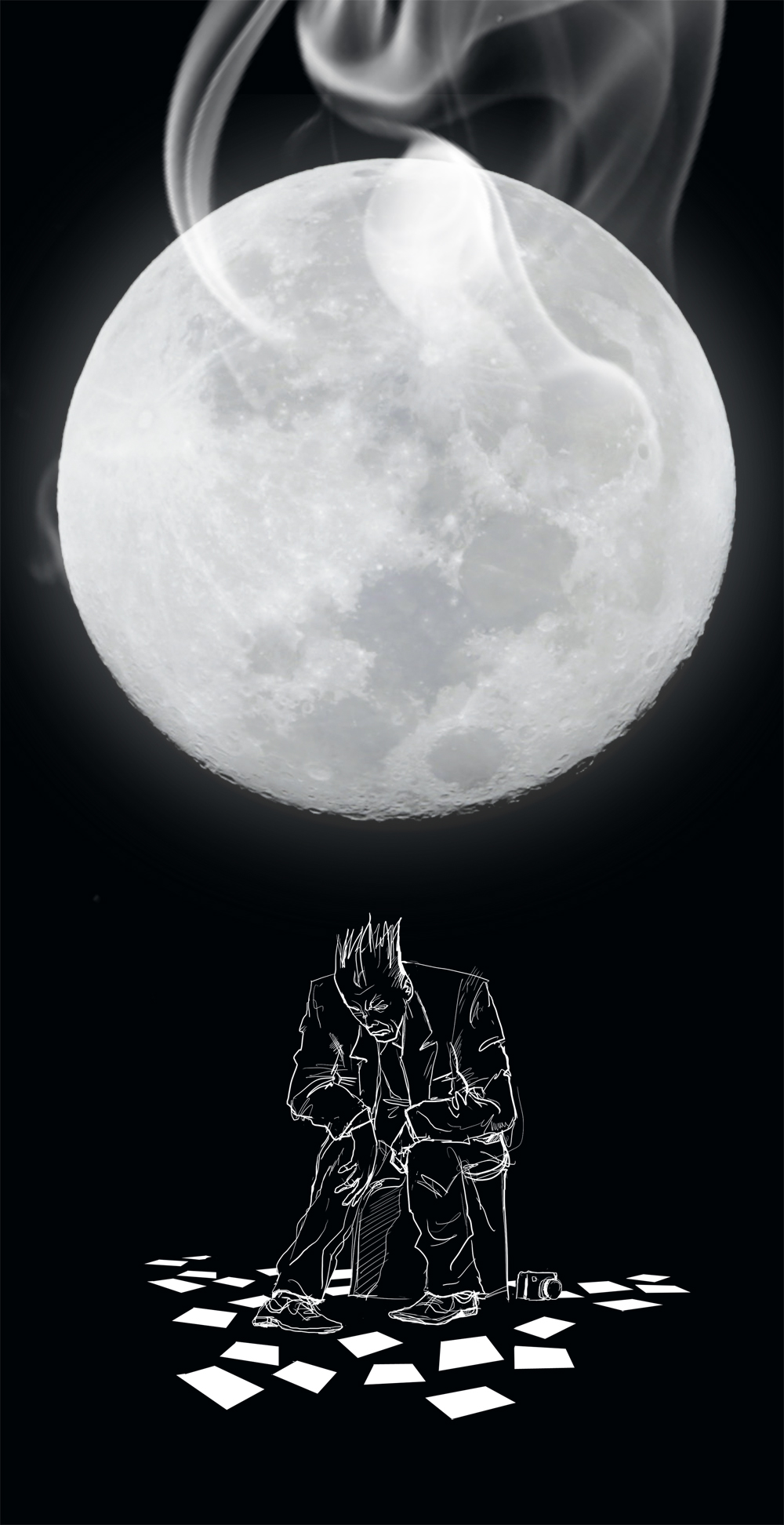

Hou Yi got up and leaned out of a window. The cold air washed over him. In the sky was a full moon. It looked cold too, like a slip of ice. He wanted to photograph it for his wife but she would have seen it hours earlier.

How many times had they sat on the front porch of her parent's house, searching for the moon and different constellations? Oh, Ryan's belt, one of them would say and every time they found it funny. It didn't seem fair, he thought, that she could see the moon but not him, when it was so much farther away.

They could both see the moon but not each other. Hou Yi was trying to remember how far the moon was from the Earth when something landed on the back of his neck. It felt like a feather. He looked up and saw small flickering lights. Cigarette ash.

Please could you-

What?

Hou Yi cleared his throat. Please could you not-

Shh, you'll wake everyone up.

Hou Yi could hear the muffled laughter even after closing the window. He tried to sleep but the footsteps overhead were louder than usual. He picked up the camera. One touch of the zoom button and he was next to the ceiling, with one ear pressed against it.

Another touch of the button and he was released from it, back on the bed. Every time someone laughed he took a shot. His finger moved quickly. When the roll of film came back from the developer, Hou Yi collected a stack of thirty-six prints, each of which looked completely blank. More photos that wouldn't go to his wife.

Chan Ziqian, 34, works as an editor. She received a grant from the NAC Arts Creation Fund in 2012.

*According to Chinese folklore, Hou Yi was a legendary archer. Long ago, the Earth had 10 suns, which caused much suffering to the people. Hou Yi shot down nine of the suns and became a hero. His wife is Chang'e, who became an immortal after drinking an elixir and lives on the moon.

Get The New Paper on your phone with the free TNP app. Download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store now